We regularly explore the investment rationale of one of the companies we own in the Melville Douglas Global Equity Fund to articulate what we find compelling. This time around we have chosen LVMH.

According to Coco Chanel the “best things in life are free. The second best are very expensive”.

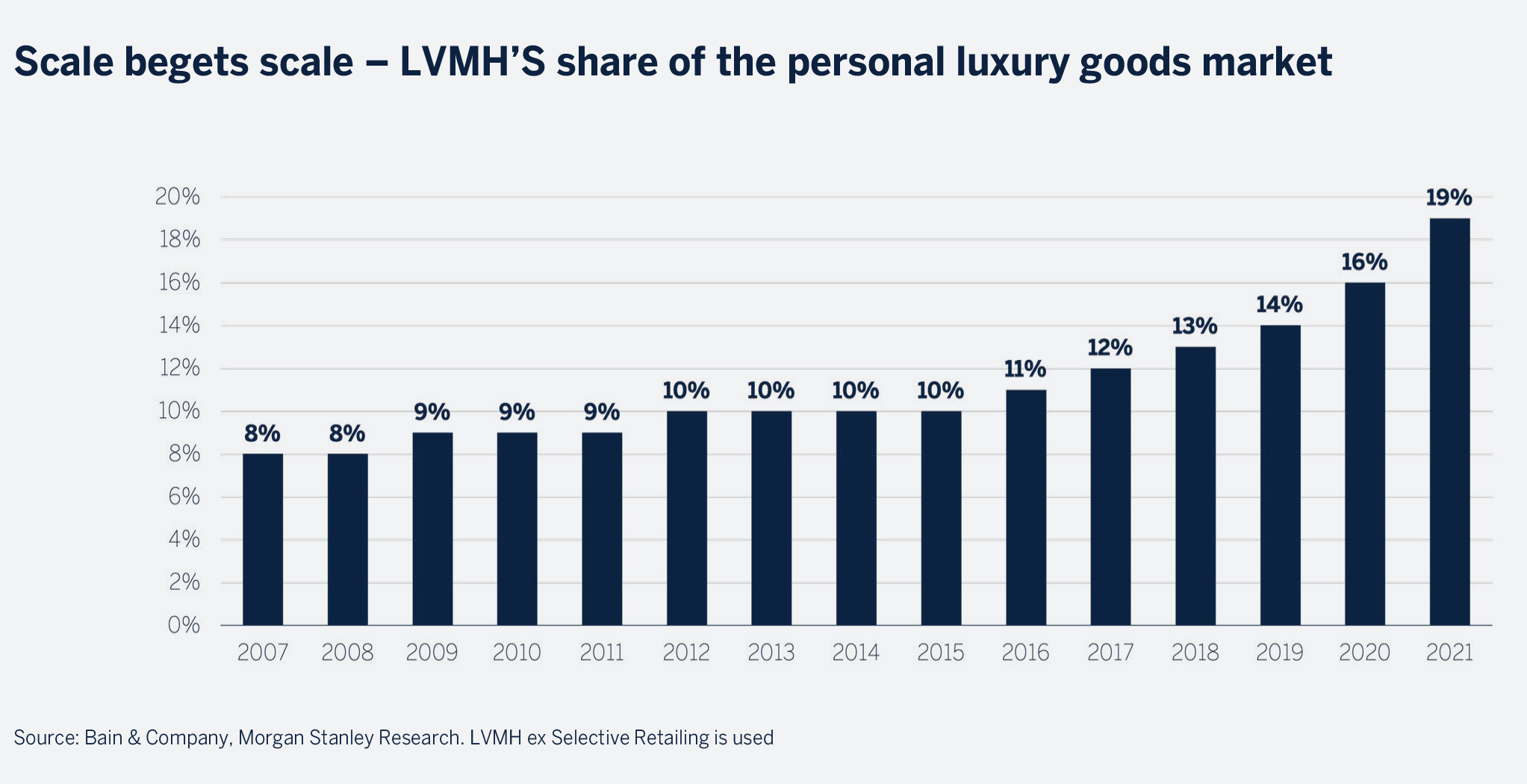

Herein is the investment thesis. LVMH’s highly profitable business model is based on selling the “best things in life” to not only the super-rich but also to a growing and aspirational middle class. Heritage is scarce and hard to replicate. LVMH’s economic moat is built around an array of some of the most enduring brands, such as Louis Vuitton (the LV in LVMH) with a 100-year history.

What Does LVMH Do?

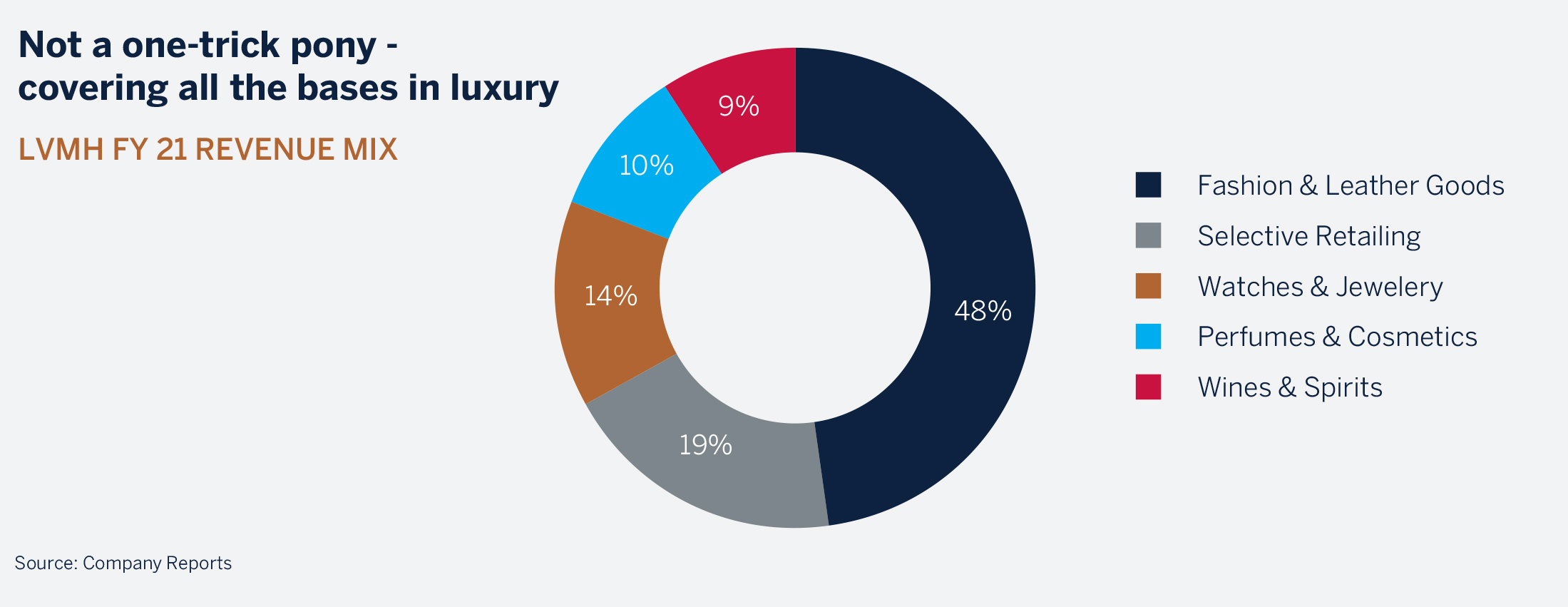

As the world’s largest luxury goods company it has unrivalled scale and diversification across a wide range of leading brands. Uniquely it has offerings across all five major luxury categories: wines & spirits, fashion & leather goods, perfumes & cosmetics, watches & jewelry and selective retailing.

The company came into being in its present form in 1987 when Louis Vuitton, a luxury fashion and leather goods company merged with Moet & Chandon (a high-end champagne house) and Hennessy (prestige cognacs). Today it is a business of significant scale with 75 decentralised “Maisons”, around 5,500 stores and over 175,000 employees.

Within LVMH the most profitable division is its fashion & leather goods division where it holds leading brands such Louis Vuitton, Dior, Fendi, Loro Piana and Celine amongst others. Louis Vuitton is the king of the mega luxury brands with industry-leading profitability, fullyowned retail distribution and large marketing budgets.

LVMH has exposure to the high-end jewelry market through the Bulgari brand and recently acquired American luxury jeweler Tiffany. Jewelry is an attractive category given the underpenetration of branded jewelry relative to other luxury products. The category also enjoys high barriers to entry as the cost of precious materials used is high and given the need for quality assurance.

In perfumes and cosmetics, LVMH is a key player with around a 10% global market share. Its portfolio includes strong heritage brands (Christian Dior, Guerlain, Givenchy) as well as up and coming brands such as Fenty Beauty by Rihanna.

LVMH has carved out high market share within the niches in the premium alcoholic beverages market. Brands like Moet & Chandon & Dom Perignon hold 20% global market share of champagne volumes (around 50% in value). The company owns half of the cognac market, led by its prestige brand Hennessy.

The Selective Retailing division provides exposure to travel retail through duty free stores and to the beauty retail channel through Sephora. Sephora has been successful in growing its store network worldwide and nurturing new brands such as Benefit within the LVMH stable. Sephora can differentiate itself by leveraging its access to LVMH’s in-house brands and exclusive distribution agreements.

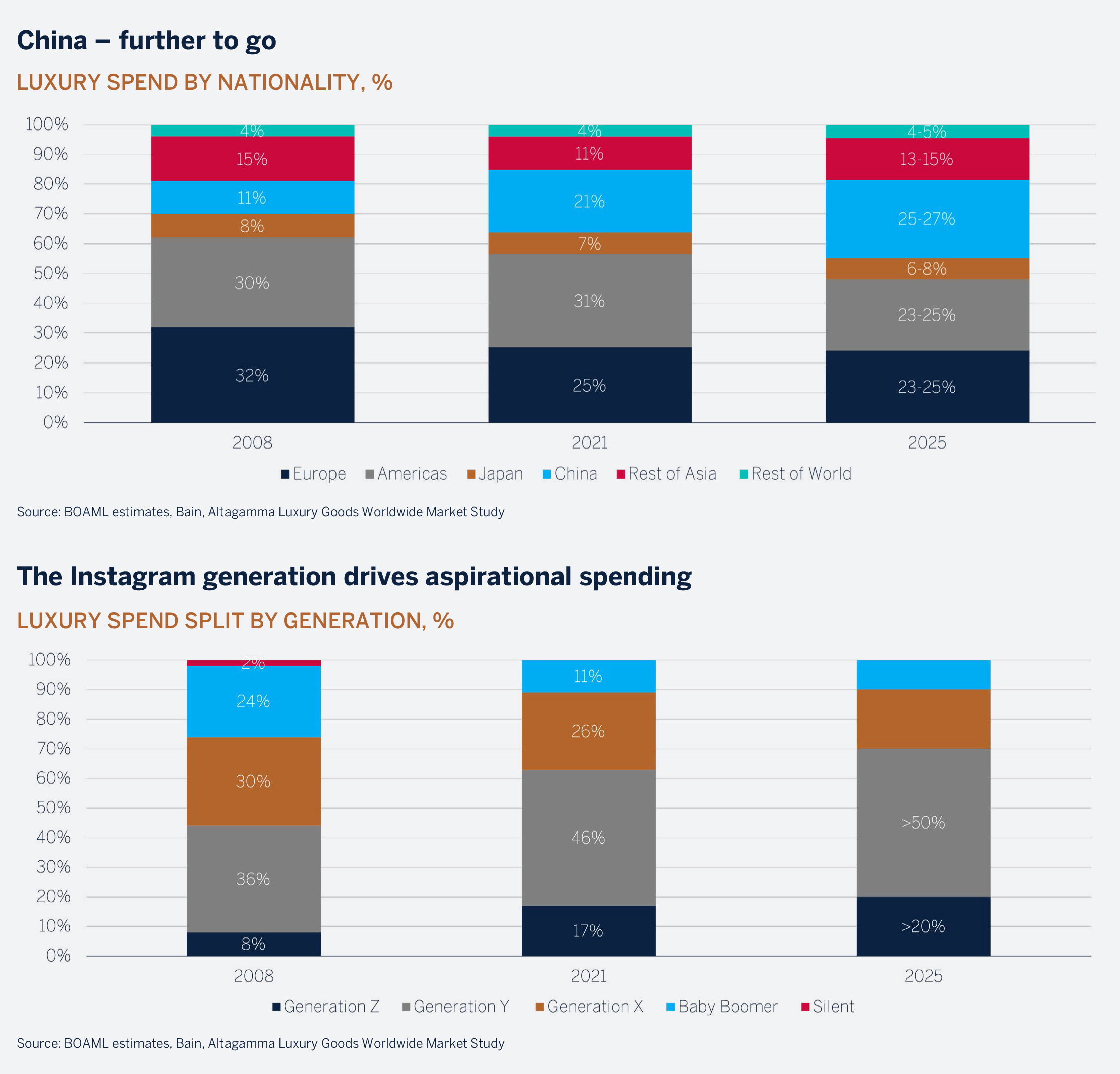

Luxury is a Play on Favourable Wealth and Population Dynamics

The luxury sector is a play on the expanding middle class: particularly in China and other Emerging Markets. As the middle class become wealthier, they become more aspirational and spend more on branded luxury goods. The number of people in China’s middle and upper-middle income class grew by 350% between 2009 and 2020. This is expected to accelerate under the Common Prosperity agenda whose polices are expected to focus on ways to improve the quality of life in China socially through wealth creation, rather than redistributing wealth. The growing wealth of high-net-worth individuals (in 2021 it grew by more than $1 trillion for the 500 wealthiest people) and the transfer of wealth to younger generations are further supportive dynamics for the industry. The younger generation has already become an important component of luxury spend. Globally millennials and Gen Z now make up 63% of luxury spend. In short, we believe luxury sector long-term growth will be supported by an expanding middle class, younger generations, and greater luxury spending from high-net-worth individuals as they become wealthier.

Louis Vuitton (LV) stands out in the luxury goods space as being one of the only brands that fully controls its distribution by selling only in stores that it owns and that are operated by LV employees. This means there are no price discounts, resulting in higher margins and ultimately protecting the brand perception. In fact, CEO Bernard Arnault has said that he would rather incinerate the products than discount.

By controlling the distribution, LVMH can edit the assortment, close down stores and introduce new products when there is brand fatigue. This was done in China a few years ago when there was market saturation of logo products. Had they been present in the wholesale channel they may have been forced to discount as their retail partners would have wanted to clear inventory, ultimately damaging the brand image. Other brands in the fashion and leather goods division, such as Loro Piana (85% of sales) and Dior (90% of sales at time of the acquisition), also have a high component of fully-owned distribution.

In wines and spirits their brands are well recognized within their categories and enjoy leading market share. This gives them negotiating power with their distributors and allows them to command premium shelf space. Dom Perignon said at the moment he discovered champagne: “Come quickly I am tasting the stars”. Consumers and distributors alike would consider a shelf of premium champagne that didn’t include names like Moët & Chandon, Veuve Clicquot and Dom Perignon far less star-studded.

On the perfumes and cosmetics side, they have good representation across wholesale channels given the global recognition of their brands. In addition, LVMH sells through their own channels via Sephora and duty-free shops.

In watches and jewelry, control of distribution has increased through the recent acquisition of Tiffany which operates through a directlyowned store model. This gives LVMH greater command of the turnaround of the brand as they launch new collections, curate the product range, and refurbish stores in line with the new Tiffany image. In Bulgari, their other jewelry brand, they have also been rolling out directly operated stores over the last few years.

When 1 + 1 = 3. Plugging into the Powerful LVMH Network

LVMH has a successful track record of acquiring and turning around underperforming brands through its network of experience and expertise.

There are numerous examples. The conglomerate acquired Bulgari in 2011 and the jewelry brand was able to double its contribution to group operating profit within 4 years from 2% to 4%. By 2019 it had multiplied its profit five times according to management. The acquisition of Christian Dior allowed LVMH to broaden its fashion and leather goods division. Christian Dior has been an outstanding success becoming one of the hottest brands of the last few years. The brand’s contribution to operating profit tripled in 3 years to 11%. It is now almost a €10 billion business.

More recently the jewelry division has expanded with the acquisition of struggling American brand Tiffany which has lost its shine over the last few years. The progress to date on the turnaround has been encouraging with LVMH reinvigorating the brand through fresh marketing, a new highly experienced management team, store refurbishment and new collections. Given its successful track record and early positive signs, Tiffany has a good chance of repeating the success of Bulgari and Christian Dior. The company’s accretive M&A can been seen in the stability of its return on invested capital relative to the peer group.

Luxury brands that are desired can achieve high margins because people are willing to pay up for products that support their identity. Luxury goods are aspirational. They represent success and owning something special and exclusive. These goods are a tangible way to show the world you “have arrived”. Price (within reason) is therefore not the main factor driving the decision when buying these goods. Hence pricing power is strong for the sector and particularly for LVMH that has a portfolio of leading brands that people aspire to.

Luxury goods is a fixed cost industry so scale matters. However, there needs to be balance between selling sufficient volumes to reach scale and maintaining exclusivity. Louis Vuitton is one of the most successful brands at walking this tight rope. The result is industry leading profitability.

Not Immune, But More Resilient Than You Might Suspect Through Cycles

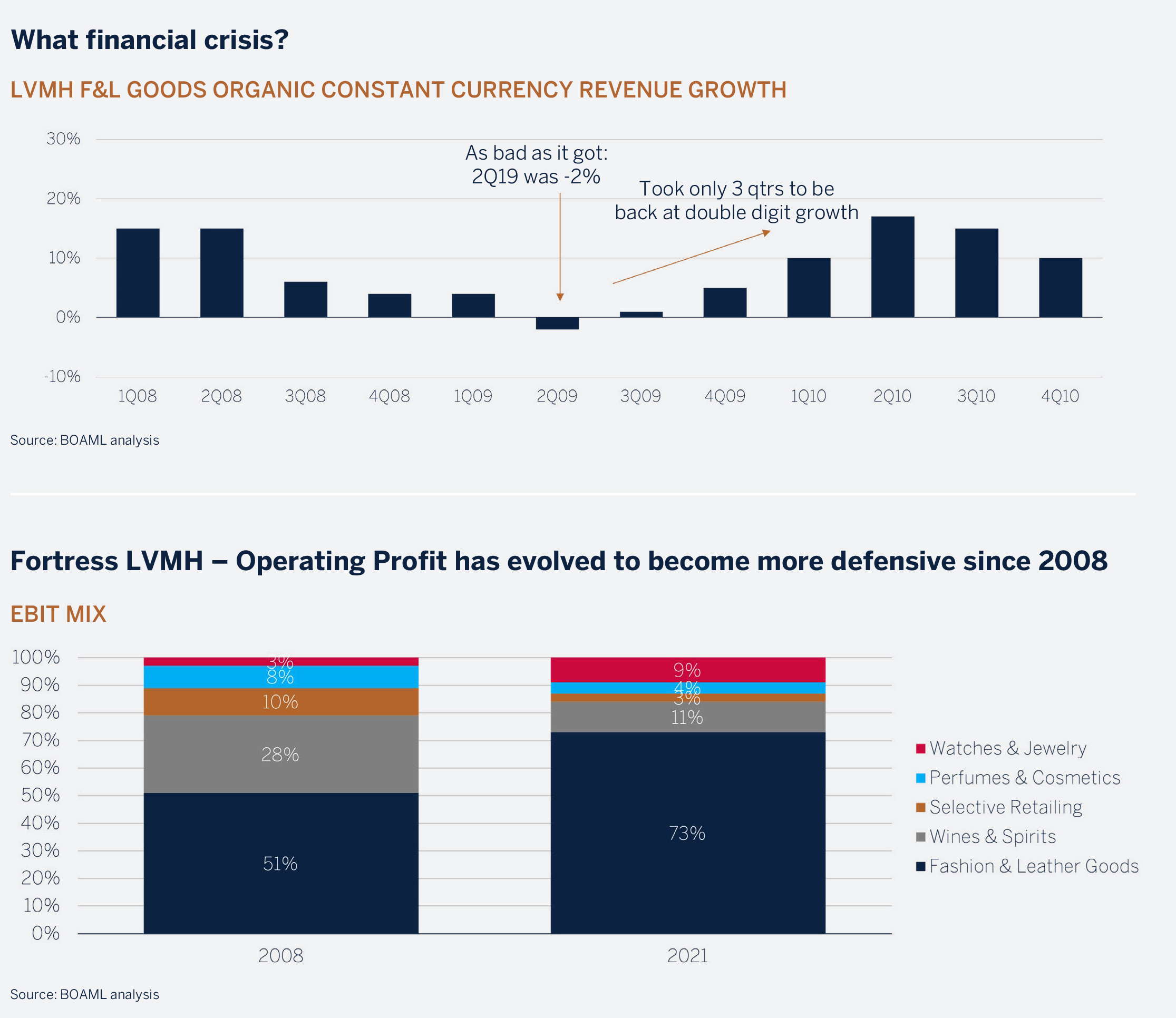

Luxury goods demand is corelated to global GDP growth. Consumers will tend to spend more when they are feeling confident and wealthy and reduce spend when they are concerned about their future wealth prospects. When we examine how LVMH was impacted by the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) their fashion & leather goods division stands out. It declined for only a single quarter over the GFC and rebounded quickly back to double digit growth only three quarters later. The sectors that were most impacted over the recession were wines and spirits and watches and jewelry given their higher exposure to the wholesale channel which was under pressure from destocking.

Compared to 2008, the business mix has since evolved. Fashion & leather goods has become a much bigger part of the business at 73% of operating profit (which is up more than 20 percent), while wines and spirits operating profit contribution has shrunk by half. Today watches & jewelry contributes more to the profit mix than in 2008, however they are now more exposed to the retail channel and jewelry (than more cyclical wholesale & watches as in 2008). Watches and jewelry now includes Tiffany which controls its distribution and is therefore not as exposed to wholesale destocking. The strength of the business model and their ability to manage costs helped LVMH show strong cash generation over the GFC. The luxury conglomerate was able to achieve operating free cashflow that was 58% above the average free cash flow in the previous 5-years.

The resilience of the business model in previous recessions and the changes made to the business mix since provides confidence in LVMH’s ability to navigate through challenging times. They can take advantage of downturns using their strong balance sheet to continue to invest and strengthen their dominance. Coco Chanel also said, “fashion changes, but style endures”. The same can be said about LVMH.