When to sell

Selling is often assumed to be the other side of the coin to buying. The presumption is that the decision-making process should be the same. But, empirical evidence finds that, for the average fund manager, sell decisions perform less well than (and detract from) buy decisions. Also, those with superior selling skills are also good buyers, but not necessarily vice versa.

Why is selling so hard?

In essence, there are more mental obstacles to overcome. These include:

1/ Regret (loss aversion)

The Cambridge dictionary definition of “regret” is a feeling of sadness about a mistake you have made, and a wish that it could have been different and better. Investors typically anchor to the original price paid or to recent peaks. This results in hanging on to losing investments for far too long on the hope of a rebound to the level they wished they had sold with hindsight. Regret is only made permanent when a stock is sold at a loss. While it is still held, there is always the chance (in one’s mind) for the investment to recover. Regret also leads to selling winners too early — presumably to avoid the potential discomfort of seeing your gains going up in smoke if the share price rolls over.

2/ Changing your mind

John Maynard Keynes famously quipped “when the facts change, I change my mind.” As well as being one of the most influential economists of the 20th century, he was a hugely successful manager of the King’s College, Cambridge endowment fund. However, most people, especially the clever and educated, are afraid to change their minds and admit they were wrong. This is likely exacerbated in a professional context where frequently flagging your mistakes is not an obvious way to self-promote your skillsets. This is true in many fields where a sense of certainty and infallibility provides reassurance (e.g. doctors or airline pilots). It is not, however, the right trait for successful investment analysis, which involves making forecasts over an ever-evolving future.

3/ Inertia

For directly held client portfolios, capital gains tax planning (e.g. waiting to sell until the next tax year) can prevent selling. It is not a foregone conclusion that a sale will be successful. By contrast, to quote Benjamin Franklin, “nothing is certain except death and taxes.” The problem is that not selling may well cost more in terms of foregone investment returns compared to stumping up a little more to the taxman.

In addition, there are less proactive forms of inertia. The “endowment effect” finds people are more likely to retain an object they own than acquire the same object when they do not own it. The most famous example is a study in which undergraduates were given a mug and then offered the chance to sell it for pens, an equally valued alternative. Once ownership was established, the students required twice the mug’s value to part with it. This behavioral bias is a problem for investment portfolios as it would stymie switching existing investments into better alternatives.

Inertia is also a result of the uncertainty and the lack of well-defined precision associated with equity investing. An investment thesis will often become less attractive at a glacial pace. This is either because the valuation has become too expensive or because there is a gradual deterioration in the long-term outlook. However, there is rarely an exact tipping point when the investment view switches from buy to sell. No one is waving a red flag. The perfect time to sell will only be obvious in hindsight. By that time, it will be too late.

How do we approach selling?

Our investment philosophy is based around holding a range of high-quality investments over the long term to best capture the power of compounding. We see ourselves as business owners rather than short-term traders of the share price.

As with buying, a clear and repeatable process is also necessary for selling. Our sell decisions need to overcome the behavioral biases described earlier.

Reasons for selling fall into three categories:

1/ The facts have changed

This is when the original reasons for holding the position have deteriorated. To avoid mission creep (i.e., changing the original thesis to justify continuing to hold the position), when we first add a stock to the portfolio, we document “red flags” that would make us change our mind. These “red flags” are regularly monitored and provide an objective sell signal. Examples include:

- Loss of pricing power.

- M&A outside the core business.

- Addressable market is ex-growth and reaching saturation.

- We have lost faith in management.

2/ Competition for portfolio capital

We purposely limit the holdings in the global equity strategy to a maximum of 35 names. The primary reason is to ensure only the highest conviction ideas from our monitored list of 60-80 high-quality compounders make it into the portfolio. We want to avoid holding a long tail of less convincing ideas.

Furthermore, because buying is easier than selling (as explained earlier), why not play to this behavioral bias? Our team regularly reviews ideas for the monitored list and new ideas for this list. We are very choosy, so not many make the grade. But when they do, that provides an opportunity to reconsider an existing position if it now holds us back from owning a potentially better idea. We consciously seek to overcome the “endowment effect.”

3/ Valuation becomes egregiously expensive

A mistake for quality-growth investors is to sell your winners too early. We are aligned with Warren Buffett’s shrewd advice that “it’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.” Quality compounders will grow through their valuations. For example, five years ago, Microsoft was trading on a seemingly elevated 30x price-to-earnings ratio. If the share price hadn’t advanced since then, it would have now been valued at a rock-bottom 13x earnings. What had happened was that the valuation stayed at around 30x, but the share price tripled, matched by the earnings growth.

However, there is a price for everything (even Microsoft). We do not seek to overtrade on valuation, but we pay a lot of attention and generally take action when valuations become stretched (two standard deviations away from the mean is a flag for us).

Experience helps

An important selling (and buying) tool is to codify our shared knowledge and experience. To quote George Soros, “To others, being wrong is a source of shame; to me, recognizing my mistakes is a source of pride. Once we realize that imperfect understanding is the human condition, there is no shame in being wrong, only in failing to correct our mistakes.”

Over the years, we have documented our lessons learned – successes as well as mistakes. We add to this ever-expanding internal booklet annually. Examples of our selling lessons include:

- Your first loss on a stock is often the best loss.

- Management teams are economical with the truth and will hope for the best.

- Think like a short-trader when considering the bear case.

- Trim at two standard deviations expensive.

- Start over with a blank piece of paper.

- Maintain a wide bench of ideas vying for a place in the portfolio.

- Large acquisitions = dead money.

- Big ships are hard to turn.

- And so on...

This collective wisdom is regularly noted at our investment discussions, shared with the next generation to accelerate their learning curve, and helps to avoid repeating the same old mistakes.

To Conclude

Our investment philosophy and process are predicated on selecting only the best compounders and allowing sufficient time for their investment theses to play out. But there will be times when we need to move on. Being humble, understanding our own biases, and having the guardrails and processes in place ensures selling is given equal billing to buying.

From our Fund Manager’s Desk

Experian

We regularly explore the investment rationale of one of the companies held in the Melville Douglas Global Equity fund to articulate what we find compelling. This time round we have chosen Experian.

If information is power and power is money, Experian has a lucrative edge. The firm has quietly amassed a data empire that underpins a wide range of critical functions in the modern economy. From lending decisions to fraud prevention, Experian’s data-driven insights are increasingly vital as the digital age accelerates. This note will examine Experian’s business model and why it deserves a place in the fund as a “Melville Douglas Compounder”.

What is Experian?

The credit information industry traces back to 1803 when a group of London tailors began swapping information on customers who failed to pay their debts. Experian originated out of the operations of Great Universal Stores (GUS), a retail conglomerate in the UK. GUS had millions of small customers who purchased goods on credit through its mail order business and home furnishing stores. In the 1960s, approximately a quarter of British families were customers of GUS. Therefore, GUS was probably the largest lender in the UK at the time. The company built its own credit databases, which were originally only for in-house use until IBM persuaded them to sell the information externally. The commercial conduit for GUS’ credit information services was formalized in 1980 as CCN Group. The business grew in part through acquisitions, including the 1996 purchase of US-based Experian, formerly known as TRW Information Systems and Services. Experian, as it was renamed, was spun off from GUS in 2006. The IPO was in October 2006 at £5.60 per share. In 2007 it added another geographical leg beyond its key US and UK franchises by acquiring Serasa, Brazil’s leading credit bureau.

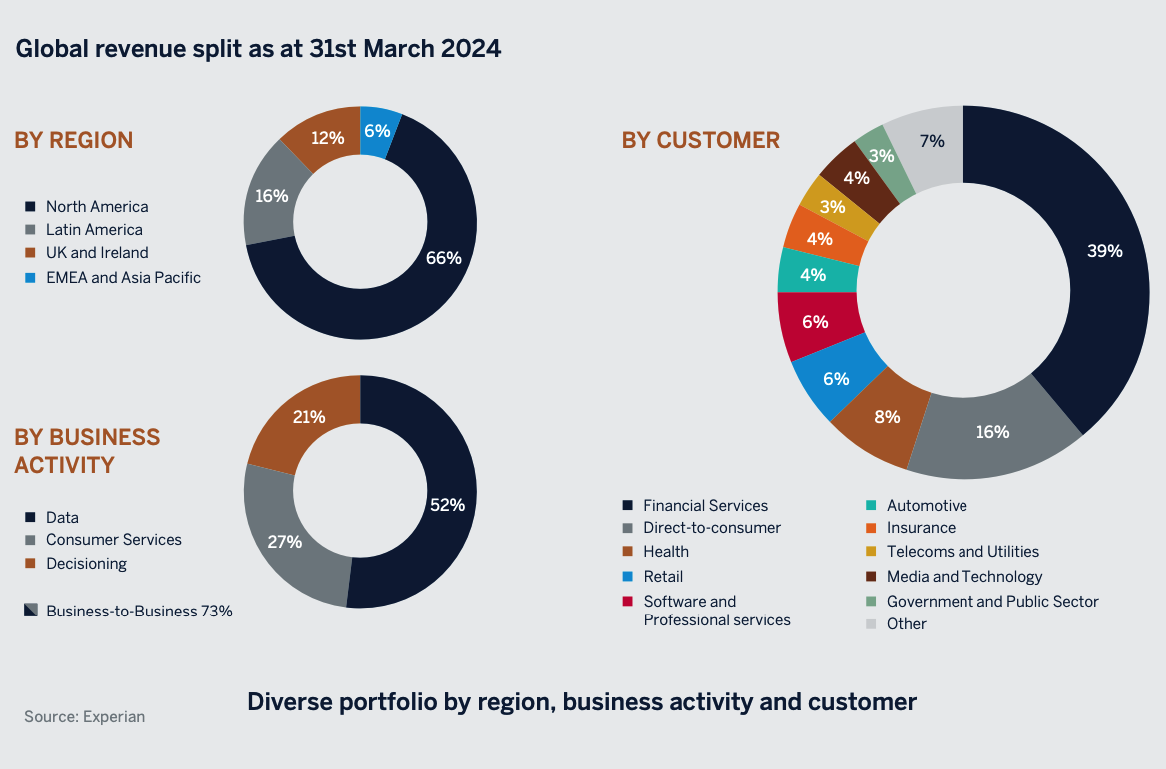

The company reports its financial results according to three segments: Data, Decisioning and Consumer Services. Data and Decisioning includes its credit bureaux and provides businesses with a suite of data driven tools and services, enabling better decisions about credit risk, fraud prevention, and marketing. Consumer Services provides credit reports and scores to consumers, empowering then to make informed financial decisions. While the competitive advantages for Experian’s other businesses are not quite as deep as the core credit bureau business, they are natural add-ons that have significantly expanded its growth opportunities.

Building on its credit database – a balanced business mix

Why is a credit bureau an attractive business model?

A credit bureau (or “consumer reporting agency” in the US) searches and collects individual credit information. The information includes credit applied for, whether or not their applications were successful, bill-paying habits and how they repaid loans. Experian acquires data from thousands of sources, including from creditors, debtors, debt collection agencies or offices with public records (e.g. court records) as well as incorporating demographic information on consumer purchasing activity. The data it collects are the foundation for credit scores used by lenders to assess the creditworthiness of a consumer.

This data is sold for a fee that is typically tiered (i.e. $0.80 per credit report for the first 10,000, then $0.75 and ultimately $0.60 for a very large number of reports). Customers include large multinationals, financial institutions (i.e. banks, mortgage lenders, credit card companies and other financing companies) and governments as well as small mom-and-pop businesses. About 39% of Experian’s revenue still comes from the financial-services industry. That proportion might sound high but is down from about 70% in 2000.

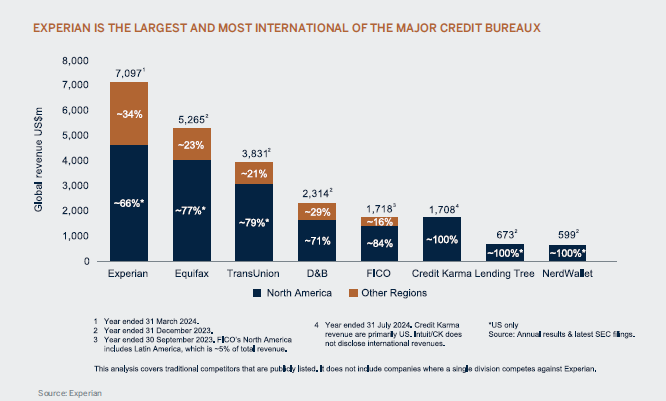

The US credit reporting agency (CRA) industry is concentrated given it is dominated by a top tier of three players. There are other much smaller CRAs, but they do not pose much of a competitive threat. The other two major players are Equifax and TransUnion, which are less global and more US-centred compared to Experian. Another significant competitor is Dun & Bradstreet, which is just focused on business lending, where it is the market leader in the US (Experian is #2). Experian is split 80% consumer credit information and 20% business credit information. Outside the US, the industry structure and competitive landscape varies. For example, credit bureaux tend to be state owned in Germany. In Brazil there is only one significant credit bureau, which is Serasa (owned by Experian). Experian is also the dominant player in the UK.

Given the concentrated industry structure, credit bureaux/CRA competition tends to be oligopolistic. Although a credit report is often a tiny fraction of a lender’s total costs, it is a crucial piece of information to assess the risk of default. Hence, the credit report industry does not need to compete on price. The market leaders tend to provide a joint service as banks and lenders usually pull credit data from more than one firm when determining the creditworthiness of consumers. The result is a highly profitable and cash generative credit reporting industry.

There are three main reasons:

/ First, there is the difficulty and expense of replicating a database of similar depth and quality. Experian has a powerful network effect, whereby businesses want to use its information, and are happy to supply it with their own, as it has the best data. This has fuelled multi-decade growth of an unrivalled database of millions of records that have been tirelessly matched and enhanced.

/ Second, there is no incentive for most banks to go to the expense of setting up data distribution to new entrants, unless there is a major pricing issue, which there isn’t. As credit bureaux data is based on the voluntary reporting of thousands of financial institutions, it is unlikely a startup, particularly amid heightened data security concerns, would be able to convince banks to share consumer information.

/ Third and finally, regulators have imposed high barriers to new entrants to ensure consumer protection. For example, the US regulator requires credit bureaux to have the infrastructure and processes in place to deal with any consumer disputes over the accuracy of their credit score within 30 days.

Steady Eddie growth

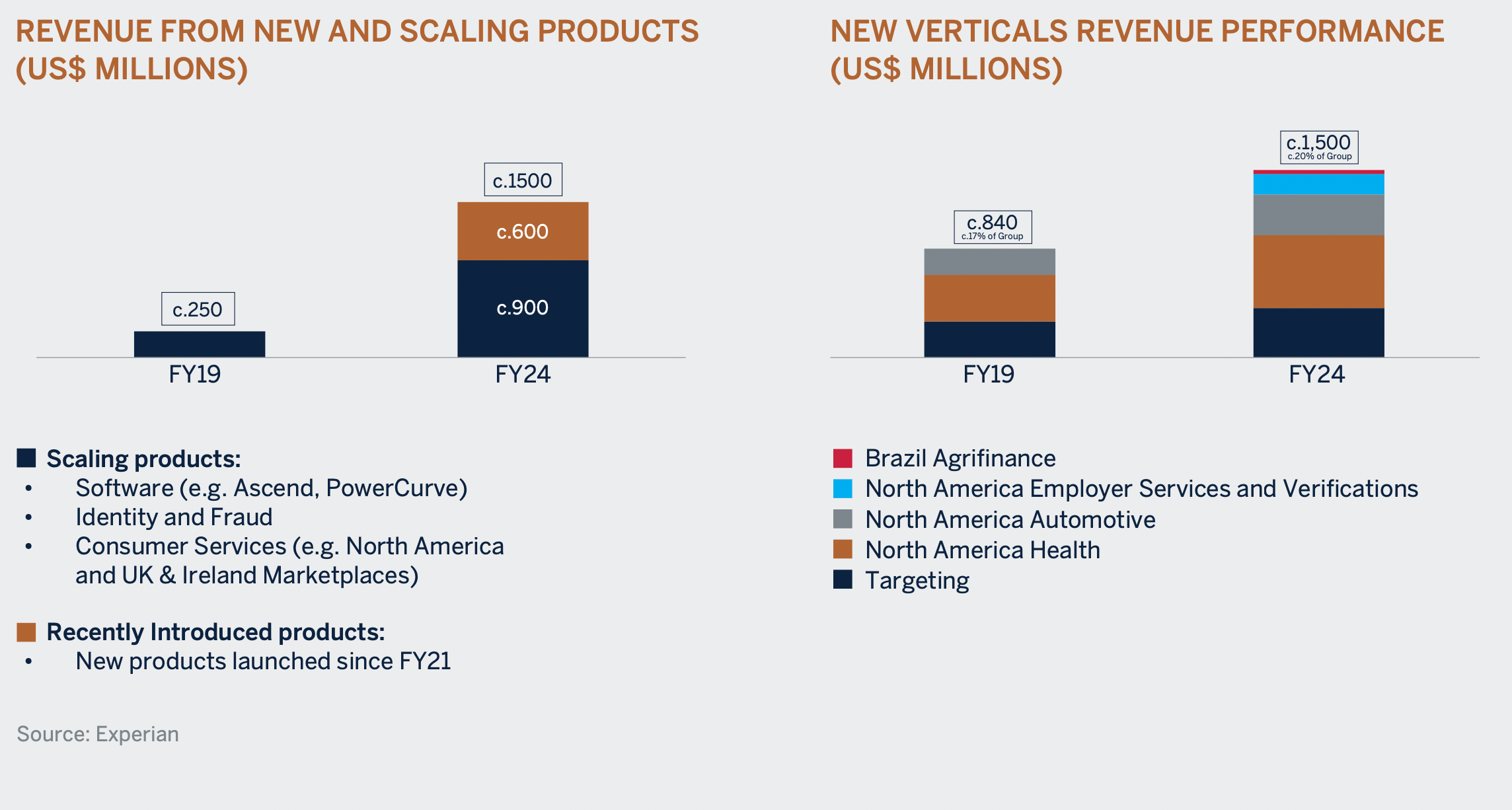

Experian’s three largest markets for its data are the US, the UK and Brazil. The first two geographic regions are expected to grow steadily. A key driver is the sale of data analytics software platforms to enable its clients to enhance lending decisions. For example, Experian’s software automates and drives the process when a person applies online for a bank loan. This includes checking the borrower’s credit status and their ability to repay the loan, applying the bank’s lending criteria, checking that applicants are who they say they are and replying with an answer within seconds for a process that previously took days. Another example is the PowerCurve suite, which helps clients deal with delinquencies (e.g. determines whether it is worthwhile renegotiating debt) and is anticyclical in nature.

There is also growth from new market segments such as healthcare, automotive and fraud detection. For example, Experian services more than 60% of all US hospitals with revenue cycle and identity management. Furthermore, Experian’s direct-to-consumer offering is an attractive business in its own right.

Brazil, where Experian is the largest credit bureau, is the fastest growing region. In Brazil, limited financial data means lenders charge borrowers significantly higher rates of interest as they are unable to determine good or bad credits. Inefficient capital allocation is detrimental for economic growth, and therefore the government has been keen to address this issue through regulatory change to make credit bureau data collection easier. Experian has been ideally positioned to benefit, as well as expanding its product and services offering in this more nascent market.

Experian continues to find new growth opportunities.

These new growth avenues and the mission-critical nature of the credit data business (i.e. lenders cannotoperate without Experian’s data) all add up to a robust business model.

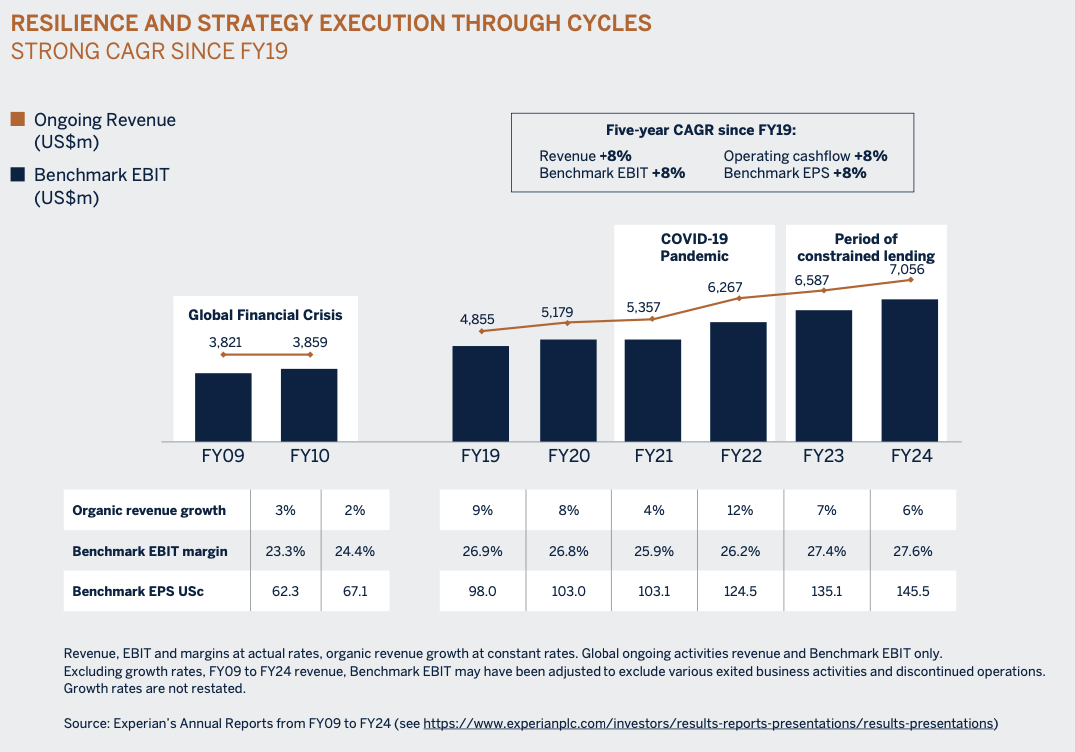

The business has proven to be resilient through the ups and downs of business cycles. Although credit application volumes slow in a recession, the core bureaux in the US, the UK and Brazil only account for around a third of group revenue. Experian has counter-cyclical protection through its risk management and asset protection offerings as well as products in healthcare and other segments.

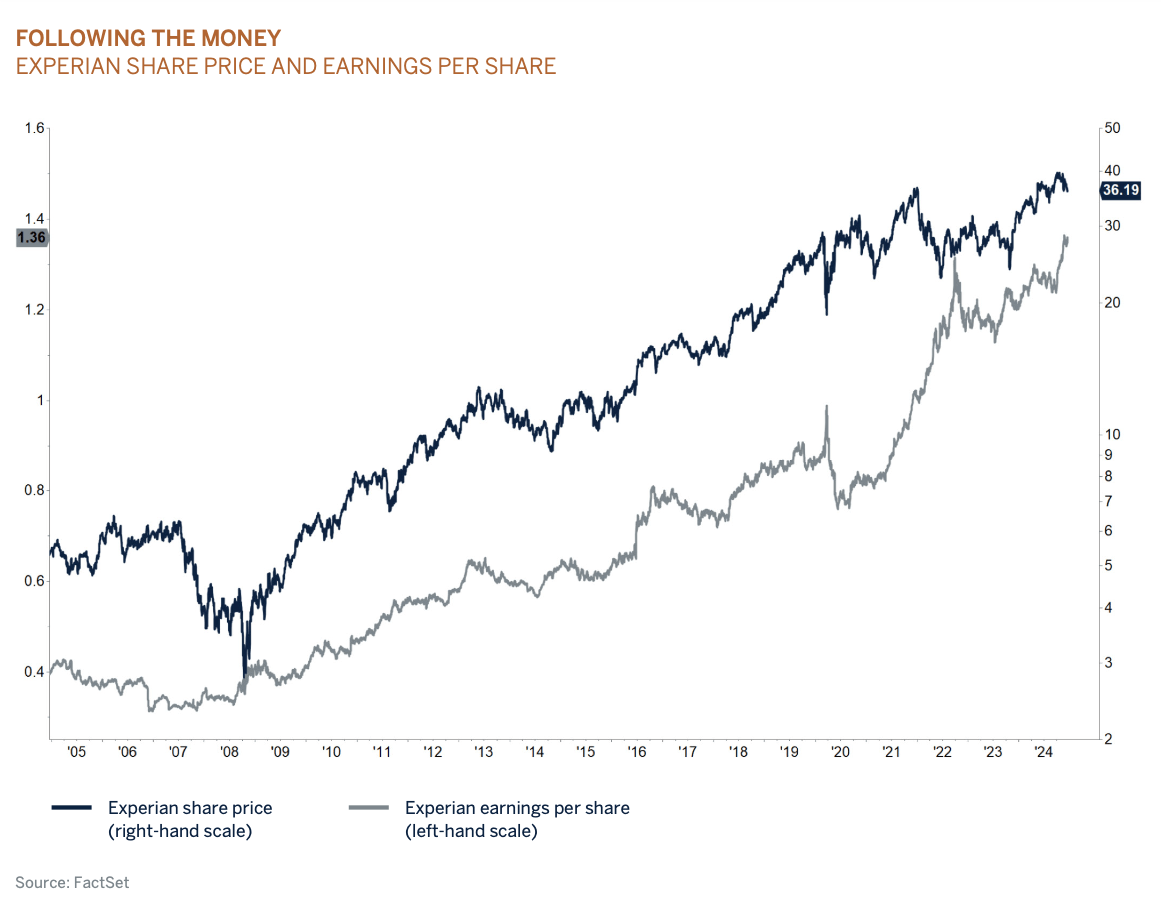

The proof is in the pudding. As shown in the chart, Experian saw positive organic revenue growth during the Global Financial Crisis, despite many of its financial sector clients running into difficulties, because there was a pick-up in demand for its credit monitoring, risk management and collections offerings.

A bullet-proof business model

When investor sentiment normalised, the shares quickly recovered and then went on to be a ten-bagger. There was a similar disconnect, albeit less extreme, through the pandemic and during a period of constrained lending when rates were hiked up in 2022 and 2023.

When investor sentiment normalised, the shares quickly recovered and then went on to become a ten-bagger. There was a similar disconnect, albeit less extreme, through the pandemic and during a period of constrained lending when rates were hiked up in 2022 and 2023.

Elementary, my dear

“It is a capital mistake to theorise before one has data.” So said Sherlock Holmes (A Study in Scarlet by Arthur Conan Doyle). It is equally critical in business.

Experian provides the information and the tools for its clients to make the right decisions. In an increasingly complex, disruptive and digitised world, the company is finding ever more opportunities to optimise its proprietary data. With a rock-solid competitive edge, multiple growth avenues, and resilience through business cycles, Experian has been (and will likely continue to be) a core compounder in the portfolio.